A Trump presidency will be bad for the world economy and worse for places outside America

IT IS not clear precisely how Donald Trump will govern, the extent to which he will carry out some of his scarier promises on trade and immigration, and who will be his economics top brass at the Treasury and in the White House. But a decent first guess is that President Trump will be bad for the world economy in aggregate; and a second is that his actions are likely to do more harm, in the short term at least, to economies outside America.

When America has in the past stepped aside from its role at the centre of the global economic system, the damage has spread well beyond its borders. In 1971, when Richard Nixon ended the post-war system of fixed exchange-rates that had America at its centre, his Treasury secretary, John Connally, told European leaders, “The dollar is our currency, but your problem.” This election result, to paraphrase Connally, belongs to America but is potentially a bigger economic problem for everyone else.

Bringing it all back home

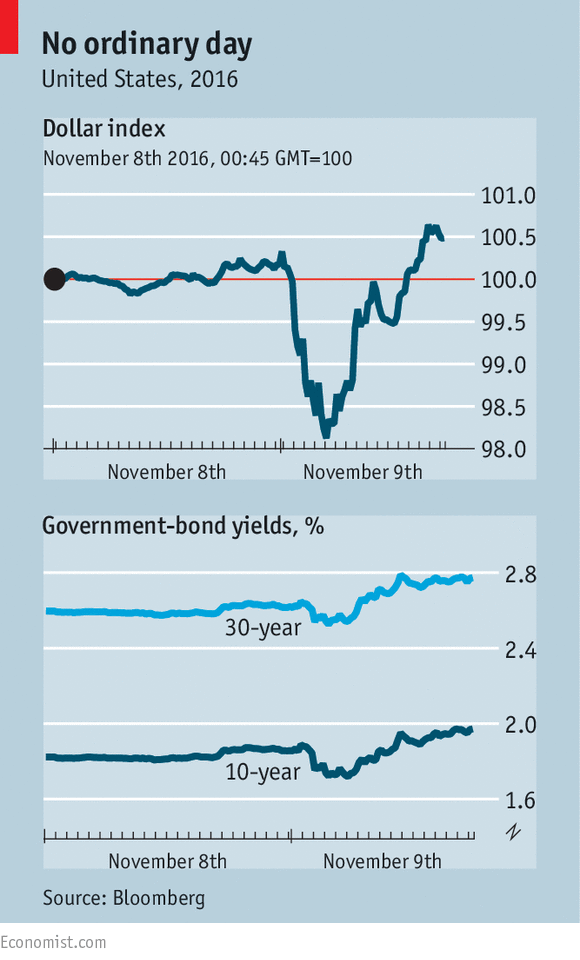

A deal between Mr Trump and Congress to cut corporate taxes, goes the logic, would spur flush American companies to repatriate retained profits held offshore. It would also allow them to increase capital spending in America, because they would have more ready cash; and consequent profits would be taxed more lightly. The larger budget deficits entailed by tax reform, along with more public spending on infrastructure, would underpin yields on long-term Treasury bonds. Indeed, after falling in the initial aftermath of Mr Trump’s victory, yields on 10- and 30-year Treasuries are on the rise again (see chart). Add the potential for higher inflation from the stimulus and the likelier use of some protectionist tariffs, plus a Federal Reserve with a more hawkish tilt, as Mr Trump’s appointees alter the complexion of its interest-rate-setting committee, and you have the makings of a renewed dollar rally.

A fiscal stimulus coupled with an investment splurge in the world’s largest economy should, all else equal, also be good for global aggregate demand. And if this kind of “reflation populism” improves the near-term prospects for America’s economy, it may dissuade Mr Trump from resorting to full-strength “anti-trade populism”. Well, perhaps. But given his leanings, it is easy to imagine him resorting to soft protectionism that keeps much of the additional demand within America’s borders. He might for instance lean on companies to favour domestic suppliers, or attach local-content conditions to publicly funded infrastructure projects. What is more, the repatriation of profits by American firms would draw resources away from their subsidiaries abroad.

In 1971 the world feared dollar weakness. These days, dollar strength tends to have a tightening effect on global financial conditions. The waxing and waning of the dollar is strongly linked to the ups and downs of the credit cycle. When the dollar is weak and American interest rates are low, companies outside America are keen to borrow dollars. Often big firms, flush with such cheap loans, will further extend credit in local currencies to smaller ones. But when the dollar goes up, the cycle goes into reverse, as corporate borrowers outside America scramble to pay down their dollar debts. That causes a more general tightening of credit.